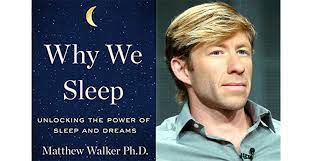

Matthew Walker, Why We Sleep: The New Science of Sleep and Dreams, Penguin, 2017 (342 pp. plus end material including index)

This is a valuable book: it is the best book I know on sleep. Significantly, it also treats of dreaming and the function of sleep and dreams in our lives. I am aware that it has been subject to strong criticism: if you check the Wikipedia page you will find the links. I must say that, from my previous reading of material in this field, I do think that Walker overstates some matters. But from what I can see, the overstatements are not significant, and will not cause anyone any harm, as they are in one direction: they stress the value of sleep. Given the seriousness of the sleep drought most of us live in, this is the only type of overstatement we should contemplate.

Let me try and sum up the book in two sentences: our culture makes it difficult for us to get the sleep and the dreaming we need to be healthy, learn to the best of our ability, and keep mentally sharp. But we can and, if we want better health, should take more care to spend in bed the time we need, and to nap during the afternoon, preferably before we begin suffering from sleep deprivation.

That is the thesis, and the book is devoted to working through the supporting evidence, and giving advice on how to sleep better. Helpfully, Walker provides twelve tips for healthy sleep in his appendix. These are basically to prepare and adhere to a sleep schedule; to exercise but not too close to bed; to avoid caffeine and nicotine; avoid alcohol before bed, and large meals and beverages at night, if possible avoid medicines which interfere with good sleep, don’t take naps after 3.00 p.m; relax and take a bath before bed,; make sure your bedroom is conducive to sleep; have appropriate exposure to sunlight; and don’t lie in bed unable to sleep. (341-342)

Before I go further, I can say that I have recommended this book to a number people, and I think the unanimous verdict has been that it has made a significant difference to their lives. This is what Walker aims: he is something of a missionary for better sleep, hence the strong words of his conclusion:

Within the space of a mere hundred words, human beings have abandoned their biologically mandated need for adequate sleep … As a result, the decimation of sleep throughout the industrialised nations is having a catastrophic effect on our health, our life expectancy, our safety, our productivity, and the education of our children. (340)

This last point refers to his radical critique of school hours, and what is expected of children and teenagers.

Part 1 is “This Thing Called Sleep,” and explains what sleep is and how our sleep changes as we age. The second part asks why we should sleep and illustrates the surprisingly diverse benefits of sleep. Part 3, “How and Why We Dream” explains why it is necessary to have healthy experience of dreams. Finally, in Part 4, “From Sleeping Pills to Society Transformed,” he explains why sleeping pills and alcohol only sedate rather than helping us obtain restful sleep, and he sets out his “New Vision for Sleep in the Twenty-First Century.”

Sleep consists of several phases. In the slow waves of NREM sleep (that sleep when our eyes are not making rapid movements), different parts of the brain share information, in what is effectively a “file transfer” (52). Recent “memory packets” are moved from their temporary storage area in the brain, where they can easily vanish, to long-term storage. This leads him to say that waking brainwave activity is primarily for reception of sense impressions, while in deep NREM slow-wave sleep, we effectively reflect upon those impressions, and distil the memories. REM sleep is a time of integration, for “interconnecting these raw ingredients with each other, with all past experiences, and in doing so building an ever more accurate model of how the world works, including innovative insights and problem-solving activities” (53). This is why sleep helps us not only learn better but remember what we have learned for longer.

Now REM sleep is necessary for the integration of our impressions with our cognitive frameworks (to paraphrase Walker). And alcohol is “one of the most powerful suppressors of REM sleep that we know of” (82), and can even cross the placental barrier and damage the unborn child (and adversely affect its sleep). Alcohol taken by a breast feeding mother is consumed by her child, and interferes with its sleep (84-85) It is easy to see why Walker recommends less alcohol, and even that amount be taken before lunch.

It is sober news for those who often wake before they have had eight hours sleep, that the most important sleep for motor-skill enhancement, is the sleep we usually have during the last two hours of it (127). Sleep deprivation in childhood is a fairly sound indicator of later drug and alcohol use, and is associated with psychiatric illness – but what Walker argues is that poor sleep may be a factor in developing these illnesses (149-150). He emphasizes that this does not mean that all such problems are caused by a lack of sleep, but that sleep is a much neglected in causation and maintenance, so that improving sleep by cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (see the twelve tips) can alleviate psychiatric problems (151).

I will end with one point which, I think, shows how deeply Walker has gone. We have all noted the often bizarre nature of what we see in dreams. This may be a function of how sleep “builds connections between distantly related informational elements that are not obvious in the light of the waking day. … It is the difference between knowledge (retention of individual facts) and wisdom (knowing what they all mean when you fit them together)” (227). I think this may go some way to explaining the strangeness of dreams: perhaps the brain is experimenting with fresh and otherwise unthought of combinations.

I could have written a much longer review, but this has, I think, shown the importance of this volume.