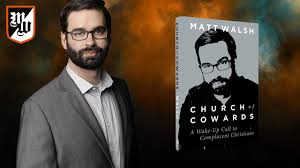

Matt Walsh, Church of Cowards: A Wake-Up Call to Complacent Christians, Regnery Gateway, Washington DC, 2020, 184 pp. plus notes, index and biblical index.

This is a strong book by one of the most trenchant and witty e-commentators known to me. There is a hardly a statement here a reasonable and well-informed person could disagree with, and some of his insights are deep and searching. Those familiar with Walsh’s work know that he appeals equally to one’s intellect and conscience. The chief criticisms of this book lie in the incompleteness of his solutions: what we need, I suggest, is the threefold path of purgation, illumination, and unification. This must be practised as a coherent whole. We need to worship at a God-oriented liturgy, with an orthodox understanding of what the liturgy is, and a knowledge of how to practice the virtues and weed out the vices. The integrity of the religious path, and the centrality of the worship of God, is more important than Walsh may realise. Yet nothing in this volume contradicts this understanding: my critique, a very mild one, goes to the clarity with which Walsh realises this.

The basic thesis of the book is that Christians are in need of the almost forgotten virtue of courage, and that if we choose selfishness and the cowardice which flows from it, we are really rejecting God. Walsh does his best to bring out what refusing the Lord and His call means in today’s world. His conclusion that to abandon courage is to abandon God, is a stark and sobering one. Because he studies the contemporary world, this moderate volume also serves as an introduction to the culture, what is wrong with it, and why Christianity can right it.

There are twelve chapters. The first is quite humorous, but almost bitter, too: he imagines a heathen horde arriving in America with the purpose of killing Christians. But the assassins are disappointed, for Christians are not be very much in evidence, not in the lives of self-styled Christians, and certainly not in the standard modern “Christian” church or meeting. He writes that the heathens, dismayed at the absence of Christian content would conclude: “If this is Christianity, it’s far too weak, self-centred, and effeminate to make killing its adherents worth it.” (5) They would return to their homeland, having wasted their time: “they had travelled all that way to persecute a corpse.” (11) It’s something of an overstatement, but a fair way of making the point.

Chapter Two makes the argument that we are hurling along “the broad road that leads to destruction.” (14) He reminds us of the busload of Egyptian Christians, men and women, young and old, who were captured by Islamist militants, and offered a choice: convert or die. They all chose death. We could hardly affirm that we would do the same when “the average American Christian has never given up one single thing for Christ.” (18)

I have long thought that the rigid dichotomy Luther drew between faith and works was false, and often wondered why more people did not think so. Lo, and behold! Walsh makes just this point in “Just Believe,” the third chapter. These pages (34-36) are excellent. Walsh also concisely differentiates “faith” from “belief” in that “Faith is a complete investment and surrender of the self to God”, while belief is only acknowledging that something is probable (28). We are called not merely to believe but to have faith. (29) There are only two ways of travel – towards or away from God (30), an ancient Christian teaching found as early as the first century in the Didache.) This means that we have to strive towards Christ, to follow, to make our hard way over long and tiring roads. (31)

Our following of Christ requires obedience, and “The de-emphasis of obedience is a terrible thing because it is a de-emphasis of the life of Christ.” (37) With obedience must go love, for it is through the love of God “I develop the substance that will fit me for heaven By choosing to accept His love, my very nature changes and I become not the sort of person who deserves to enter Heaven … but the sort of person who can enter it.” (41) This leads to the profound consideration that it is because God wants our love and not merely our belief that he does not overwhelm us with evidence of His existence; for love must be a question of choice (41). The Lord’s ministry taught us what it is to love, and of what it consists; then He exemplified love by carrying His cross (42).

Walsh’s third chapter, “My Buddy Jesus,” reminds me of Stephen Prothero’s American Jesus. He takes issue with the way that people wilfully overlook how often Scripture speaks of us as children, servants and slaves, and concentrate on the term “friends,” used once; and even then, “friendship” it is turned into being a “peer.” As Walsh says, “… our friendship with Christ is nothing at all like our earthly friendships.” (44) The Lord came to purge us of our sins, not to approve of them. (45) This distortion plays into the apparent transformation of our churches into “some sort of social club.” (46) The result is that: “Reverence and sacredness have been drained out of church, starting with the buildings themselves.” (46) In what may be one of the most telling observations in the entire volume, he states: “Church has become an extension of secular culture rather than an antidote to it.” (47, my underlining) He is entirely right to contrast, the overt and abject piety of Muslims with the casualness of Christians, not to the favour of the latter (50). I share his dislike of the phrase, a “personal relationship with Jesus” (52-53). It can only mislead: our relationship with the Lord cannot be personal like others. It is unique, and it is dangerous to assimilate it to other “personal” relationships. Finally, in this wonderful chapter, he declares: “The consequence of living in a secular age is that secularism is the default setting” (54).

“The Gospel of Positivity” is dealt with in chapter 5. The key points for me here were that: “God will always give grace and strength to those who ask for it, and even to those who don’t ask for it” (71); and – most of all – evangelists of the “Prosperity Gospel” conclude that “Jesus died not to free (us) from sin but to free (us) to sin” (76). Finally, joy is found through suffering, not by the vain tactic of denying or avoiding it (77-78).

To be continued,

Joseph Azize,

6 August 2020, The Feast of the Transfiguration