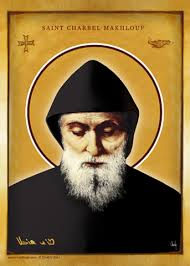

St Charbel, Third Sunday of July

Born Youssef Makhlouf in Beqa Kafra on 8 May 1828, he was the fifth child in a family of simple farmers. When he was three years old, his father was taken away by the Ottoman Army, never to return. Youssef was sent to the village school, and as a child was given to prayer. At a young age, he knew that God was calling him to become a monk. He prayed to Our Lady to make it come to pass. Two of his mother’s brothers were already monks. However, he did not leave until 1851, when a woman indicated her desire to marry him. Saying nothing, he left home the next morning to enter the monastery of Our Lady of Mayfouq, which was run by the Lebanese Maronite Order (“the LMO”). However, he was pursued there by his uncle, mother and relatives. They begged him to return home, marry, work and look after them. Charbel refused, saying that God wanted him entirely. It is said that in the end his mother gave her consent, telling him to be a good monk, but if he was going to be mediocre, then he should return home.

He took the name of Charbel, a martyr saint who had been put to death by pagans about the year 107 in the early years of Christianity. At the end of his first year, our Charbel was sent to St Maroun’s at Annaya for the second year of his novitiate. There he made his monastic profession and took the three solemn vows in 1853, when he was 25 years old. When his mother came to visit him, he refused to meet her, but rather spoke to her from a window three metres about the ground. In those days, the laws against monks speaking to any women were rather strict, and Charbel was determined to keep them. When she asked why he did not wish to meet her, he replied only that if God wished it, they would be together for eternity.

He was then sent to the Monastery of St Cyprian in Kfifane, the LMO’s scholasticate. There he studied philosophy and theology, being ordained a priest on 23 July 1859, at the Patriarchal residence, Bkerke. He was then sent back to Annaya, where he spent 16 years in the community. When he arrived there after his ordination, his elderly mother and his relatives were present once more, to greet him as a new priest, and to invite him back to Biqa Kafra to say Mass. He refused. At the end of that time, he chose to retire to the hermitage. It is said that this occurred after the miracle when his lamp remained lit although it contained only water, and no oil.

As a hermit, he was always kneeling before the Blessed Sacrament. He treated everyone with respect, even the lowliest person. He fulfilled his fasting duties honourably and to the full, even fasting more than was required. Another interesting story about him was told by Fr Ignatius Daher, who saw him digging in the fields. Just as he raised his pick in the air, a companion, Fr Makarios, called to him. Charbel lowered the pick at once, not swinging it into the ground. It is the mark of a master to completely obey even if he has got a momentum up; a master of the spiritual life is able to refrain from doing. That is, only the one with true mastery over himself possesses the ability to cease something in mid-movement, or to cease speaking mid-word. Most of us would have let the pick come down, as being the easiest thing in the circumstances. We can’t stop ourselves speaking: he could stop himself acting.

From what must be the period when he was a monk, there is a story that when he was working in a remote part of the fields with his brethren. He did not hear the call to lunch, and so he continued working. Only six hours after lunch did someone ask him why he had not eaten. Then they learned what had happened: as he ate only one meal a day, he had gone thirty hours without food, working non-stop. Another story goes that one day, again in the fields, a monk heard Fr Charbel cry out for help. The monk left his wheelbarrow, and went to Fr Charbel’s aid. When he reached him, he found him calm and silent. Charbel told him that he was alright. A little later he heard Charbel call again, so the monk returned and insisted on knowing what was going on. Quietly, Charbel said to him: “Please forgive me brother, I have been sorely tempted. Pray for me.”

In yet another example of the importance of being stronger than the body, Charbel wore the poorest clothes, never added extra clothing or wore thicker robes in winter, and ate the worst food: crusts and fruit of the meaner sort. He was vegetarian.

One would hesitate to vouch for the truth of some of the stories. But this one sounds true: a Muslim had lost his tobacco pouch. One of the monks told the man that Charbel the monk had taken it. The Muslim marched up to him and demanded it back, saying that others had seen him. Charbel’s reply was: “Do you see that rock down there at the bottom of the garden? It’s been there for centuries and no one has taken it.” The Muslim got the point: people don’t take things they have no purpose for. St Charbel, whom he knew did not smoke, would not have taken the tobacco.

Each day, Fr Charbel prepared his Divine Offering (Mass) with great care, and attended the Masses of the other monks, although this was not compulsory. He spent hours before the Eucharist, often for much of the night. He would daily say the prayer: “Father of Truth, your son is here, a victim ready to do your bidding.” This is very significant: it is easy to concentrate on St Charbel’s miracles and actions and to forget that the service of the Eucharist was the centre of his life, and that he saw it as God coming down among us, Jesus Our Lord in his body, blood, soul and divinity. It is not merely some sort of community celebration.

Fr Charbel remained in the hermitage until his death. The circumstances of this are quite striking: on 16 December 1898, he was celebrating Mass in the chapel of the hermitage. As he held aloft the chalice for the major elevation, he was struck by paralysis. The prayer at that point is: “Father of Truth, behold your Son, a sacrifice pleasing to you. Accept this offering of him who died for me. … Behold his blood shed on Golgotha for my salvation. Accept my offering.”

The final illness lasted for eight days. He left this world on 24 December 1898, the vigil of Christmas. I will deal with only one his miracles (or, more precisely, one of the miracles worked through him): and that is how his body was incorrupt for more than 60 years after his death. This may be one aspect of the mastery of the body which can be achieved by hermits. My own guess is that the body actually changes, by the grace of God, it becomes a more obedient instrument, and less subject to carnal laws: hence it is preserved for some time after death. But this can only happen by the will of God, and it exclusively occurs with saints of heroic virtue, the sort of person of whom we can say that they have pleased Him.

There is not so much to say about St Charbel’s life for the simple reason that all he did was live like a monk and then a hermit, fulfilling his duty to the utmost. He wrote no books, composed no music, and had no name in the world. The Maronite saints are often distinguished by this simplicity: while leading the most ordinary and unexceptional lives, they remained in the presence of the divine, which means that the ordinary and the unexceptional becomes infused with and permeated by the extraordinary and the truly exceptional. In that respect, they are saints for ordinary people: they were sanctified by doing simply things in a spirit of holiness.

St Charbel was the first Maronite saint to be canonised under the modern rules. This occurred on 5 December 1965. His feast is observed on the third Sunday of July each year. Prior to this, Maronite saints were canonised by the acclamation of the people, which had been the tradition throughout all the Church.

Hymn to St Charbel

to the tune of “noohdeekee salam”

| 1. Stars of the night sky shining around you,

while the moon makes a throne fit for Our Lady. Raise your holy hands and pray for us Saint Charbel!

2. Snow fell upon your head in Annaya, while your plea rose above like a plume of incense. Raise your holy hands and pray for us Saint Charbel! |

3. Nights in your hermitage, wakeful and attentive, with the Lord in the Host on his holy altar. Raise your holy hands and pray for us Saint Charbel!

4. Death comes to ev’ryone, as it came to Charbel, while he prayed in the Mass to the holy Father. Raise your holy hands and pray for us Saint Charbel!

|