To celebrate the Divine Liturgy ad orientem is to celebrate towards the East, with the priest and the faithful all standing before the altar. The opposite tradition is called versus populum, that is, with the priest facing the people. It could well be that in no Catholic Mass is the liturgy ever entirely one or the other.

I shall take just two liturgies to compare: the present Maronite Liturgy in the Book of Offering (2012), and the one from the Missale Romanum of 1962, as republished by the Angelus Press, 2004.

The Maronite liturgy alone has obligatory prayers for the Presentation of the Offerings in the sacristy, before lighted candles (BO 1). Both liturgies have vesting prayers (BO 2-4, MR omitted). The Maronite rite provides for a liturgical Lighting of the Candles at which the congregation sing (BO 5). The Maronite rite has a hymn before the liturgy commences: this is sung by the entire congregation (BO 7). At this stage, the question of ad orientem or not, does not pertain.

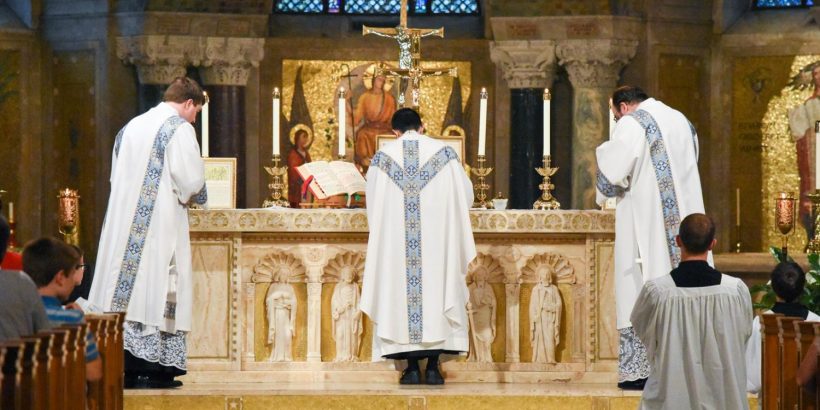

In both liturgies, the priest approaches the altar with the servers, and at the foot of the altar, says prayers, facing the altar (BO 9; MR 838. So at this stage, in both rites, the priest is ad orientem. Then he mounts to the altar for the Liturgy of the Word, i.e. up to the Gospel (BO 9; MR 844).

In the Maronite liturgy, precise instructions about the direction cease. Rather, he stands first at the Gospel Lectern, and then he blesses the people (BO 10). Generally, he will be facing the people at all these points, unless there are people in the church beside or behind the priest (as at Our Lady of Lebanon, Harris Park).

In the Latin Mass, the priest bows to the altar, then proceeds to the Gospel side. If there is no censing of the altar, he prays the Introit, Kyrie, and Gloria ad orientem, but immediately before the Collect, “turning towards the people (he) says: “Dominus vobiscum.” (MR 848).

Let us pause there: the priest turns to face the people in the Latin Mass when he is blessing them. Why? No reason is stated, but it must be because he is addressing them, since the other prayers said between the mounting to the altar and the “Dominus vobiscum” are all addressed to God, with the possible exception of the Introit which is – in its terms – simply a prayer with a Psalm and a Gloria. So the Introit could be taken as something said to or with the congregation. But in the Low Mass, the usual weekday Mass and often the form of the Sunday Mass, it is said silently. The prayer is not said to be heard by the people, although they are encouraged to read it, and in other Masses, they hear it chanted.

Knowing that, when we turn to the Maronite liturgy, we find that there has been a back-and-forth. The opening blessing glorifies the Trinity, but it is not addressed to them. The opening prayer for the Consecration and Renewal of the Church is addressed to Lord, from beginning to end (10). Most of the Opening Prayers are addressed to the Lord Jesus, but not all. For example, on Pentecost Sunday and on The Commemoration of the Righteous and the Just, the Opening Prayer is addressed to the Father (BO 159). On Sunday of the Most Holy Trinity, it is, of course, addressed to the Trinity (BO 418). This is an interesting study: the twelve weekday Masses of Pentecost are all addressed to the Sin except for Friday A, Monday B, Wednesday B, and Thursday B which are addressed to the Father (BO 475, 504, 524, 534). But – although the Maronite rite has some considerable variety in this important particular, one thing is constant: the prayer is to be chanted aloud, and in the vernacular.

Even at this early point, we can find two important principles: first, it seems that when the people are directly addressed, whether in the Latin or Maronite rite, the priest faces them. The second is that whereas in the Maronite rite, the prayers are intended to be heard and understood by as many of the people as possible, in the Latin rite this is not the case.

We then come, in the Maronite rite, to the priest’s blessing of the people (BO 10). This is naturally done facing the people, as it is in the Latin rite: when the priest says the “Dismissal” (Dominus vobiscum, … Ite missa est …) he faces the people. Then he turns to the Cross to begin “Benedicat vos omnipotens, Deus” (may the omnipotent God) and then turns to the people to impart the blessing he has sought from God (MR 916 and 918).

This provides us with a third tentative principle, common to both rites, that when the people are to be blessed, they are faced.

Now, whereas the Gloria is said by the priest alone in the Low Mass, it is said by the congregation alone in all Maronite liturgies (BO 10; MR 848).

Then, in the Maronite liturgy, we come to something which is one of the distinctive features of the Syriac liturgies, and as such is lacking from the Latin Rite: the Hoosoye or “incense prayers for forgiveness.” The prayer is spoken in the name of the entire congregation: this is quite definite, and not merely stylistic, a fact which is marked by the censing of the altar, the clergy and the congregation (BO 11). Without attempting to over-simplify this relatively rich body of material, we acknowledge our sinfulness, affirm the basic truths of the faith particularly as relevant to the celebration of the day, and seek God’s forgiveness. The prayer is also chanted by a deacon, although it can be chanted by anyone from the congregation.

Each Hoosoye is first addressed to the people: “Let us glorify, honour, and praise the Wise Builder …” (BO 11). Then it addresses the persons of the Trinity, usually but not always Second Person of the Trinity (e.g. on Pentecost Sunday it addresses the Father, the Son, and then commences a relatively lengthy prayer to the Holy Spirit, and on Trinity Sunday it is directed to all three, BO 409-410, 419). The deacon faces the people, in accordance with our second principle, but the priest faces the altar for the censing of the altar, and the congregation for their censing. Then, when the celebrant has completed the censing, he returns to his seat. In most Maronite churches, but not all, this is in the sanctuary, but sideways to the people. To my knowledge, in Sydney, only in Our Lady of Lebanon, Harris Park, does the priest sit opposite the people: in all other churches, he is sideways. But the BO does not specify anything. The principles above suggest that if the priest is chanting the Hoosoye, then he should be facing the people, but otherwise, he should not be.

To be continued