One of the most controversial figures in early Church history is St Ignatius of Antioch. He is impossible to define: he was a prophet and had an esoteric, even mystical bent, and yet he was a firm believer in the ecclesiastical hierarchy of bishop, priest, and deacon: and the obedience and responsibility which in the hierarchy prevails. He was close in time to the apostles, yet he is a witness to a church order which non-Catholic and Orthodox historians believe must have been established much later by priests trying to substitute a rigid institutional religion for the free-spirit religion which they think Our Lord intended (if they believe that He intended anything). He wrote his letters in Greek, he lived in Syria, but his name was Latin. No one knows how to understand this mix.

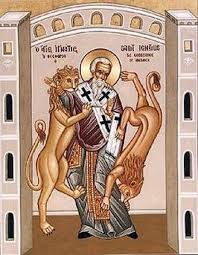

St Ignatius, who refers to himself as “the bishop of Syria” (Romans 2.2), was important in the Maronite tradition: his letters were retained and studied, and an Anaphora of St Ignatius remains, although it has not yet been translated out of Syriac. The saint was martyred in the reign of the Emperor Trajan (98 to 117). Eusebius in his Ecclesiastical History says about St Ignatius: “The story goes that he was sent from Syria to Rome to be eaten by beasts in testimony to Christ. He was take through Asia under most careful guard, and strengthened by his speech and exhortation the diocese of each city in which he stayed.” The ancient evidence suggests that Ignatius was martyred by 116. The date is believed to have been 20 December.

It is not known exactly why Ignatius was sentenced to death. It is believed that his condemnation occurred after an earthquake which shook Antioch on 13 December 115, while Trajan was in the city.

There are seven authentic letters of Ignatius of Antioch, written while he was on his way to Rome to be put to death: to the churches of the Ephesians, Magnesians, Trallians, Romans, Philadelphians, Smyrnaeans and to Bishop Polycarp. To give you a taste of his writing, this is the opening of the Epistle to the Philadelphians:

Ignatius, who is also called God-bearer, to the church of God the Father and the Lord Jesus Christ that is Philadelphia of Asia, that has received mercy and been founded in the harmony that comes from God, that rejoices without wavering in the suffering of our Lord and that is fully convinced by all mercy in his resurrection; this is the church that I greet by the blood of Jesus Christ, which is an eternal and enduring joy, especially if they are at one with the bishop and with the presbyters with him, and with the deacons who have been appointed in accordance with the mind of Jesus Christ – those who have been securely set in place by his Holy Spirit according to his own will. (preface)

In his letters, he manages to bring in two concepts, time and again: the gifts we are given through the grace of God, and the salvific suffering which we have been called to. Then, as a secondary issue, he mentions the ecclesiastical hierarchy in the epistle to the Philadelphians, and even a little in Polycarp. When you grasp this framework, you immediately understand the main contours of his thought. The man’s spirit and his methodical mind come through in this.

In addition, Ignatius deals with many other issues in the body of his letters. Let us take one, celibacy. Celibacy was highly valued, for Ignatius writes to Polycarp: “If anyone is able to honour the flesh of the Lord by maintaining a state of purity, let him do so without boasting” (Polycarp 5.2). It is hard to see how one could honour the Lord’s flesh by remaining celibate unless the understanding was the Lord, in the flesh, had himself been celibate. That is, that one honours what the Lord did in the flesh by doing the same in one’s own flesh. The paragraph as a whole also endorses marriage, but urges the groom and bride to be married with the consent of the bishop, so that “their marriage may be for the Lord and not for passion” (Polycarp 5.2).

In Ephesians 3.2, he speaks of running (in harmony) with the mind of God. This is related to the idea that the bishops share in the mind of Jesus Christ, and He in the mind of the Father. This establishes a hierarchy which acts as a sort of ladder from the earth to the peak of heaven. Although he uses different words, it also ties in with St Paul in 2 Timothy 4:7: “I have competed in the noble contest; I have run the race; I have kept the faith.” We return to this central idea of harmony:

… run together in harmony with the mind of the bishop … For your presbytery … is attuned to the bishop as strings to the lyre. Therefore Jesus Christ is sung in your harmony and symphonic love. And each of you should join the chorus, that by being symphonic in your harmony, taking up God’s pitch in unison, you may sing through Jesus Christ to the Father, that he may both hear and recognize you through the things you do well, since you are members of his Son. Therefore it is useful for you to be in flawless unison, that you may partake of God at all times as well (Eph. 4.1-2)

It is good to ponder what Ignatius is saying, because it is easy to miss it: he is teaching that we ourselves come into the sight of God when we become part of the Son. That is, he is not saying that God sees each and every one of us, at all times, but that we become apparent or visible to Him when we are joined to His Son. It is a very interesting idea. This then gives new meaning to the next paragraph:

For since I was able to establish such an intimacy with your bishop so quickly (an intimacy that was not human but spiritual), how much more do I consider you fortunate, you who are mingled together with him as the church is mingled with Jesus Christ and Jesus Christ with the Father, so that all things may be symphonic in unison (Eph. 5.1)

Then follows an intriguing passage at 5.2: “Let no one be deceived. Anyone who is not inside the sanctuary lacks the bread of God.” Now the Greek original reads: entos tou thusiastēriou, which is literally “within the altar”. The word thusiastērion is derived from the verb thuō which means “to sacrifice” and “to slaughter”. So the basic meaning of our noun is “a structure on which cultic observances are carried out, including esp. sacrifices, altar …”

What does it mean, then, to say that one must be “within the altar”? I would suggest that it refers to being with those people: the bishops, priests and deacons, who serve at the altar, i.e. who are in an area separate from the people. If I am correct, this would indicate that not only Ignatius but also his readers, and most especially the Ephesians, would understand that the church had what we now a call a “nave” for the laity, and an altar and space around it for the clergy.

This is only a brief introduction to this fascinating saint.