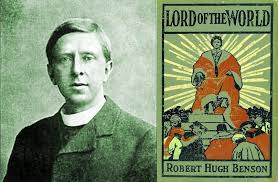

We are continuing our reading of Monsignor Robert Hugh Benson’s Spiritual Letters of Monsignor R. Hugh Benson to One of his Converts. We are considering the Anglican Letters. We have looked at the question of an act of will, and now we are ready to look at what he says about the soul.

The background to Benson on the soul is his reference to Brother Lawrence, and his classic work The Practice of the Presence of God (available in many editions and on the internet). The essence of this method is that: “… we should establish ourselves in a sense of God’s presence …” and that “… to arrive at such resignation as God requires, we should watch attentively over all the passions …” (First Conversation) This is approached in several ways, each as the moment demands, but often referred to as “conversation with God.” I think, however, “prayer” may be a complementary term: “prayerful conversation” or “conversational prayer.”

Monsignor Benson’s questions seems to be how is it even possible that we should be able to be aware of the presence of God, especially while we are doing other things? It is not as if God appears in our field of vision like a policeman, or even an icon. Are we meant to think about God?

No, says Benson, we are not asked to think about God but to be conscious of His presence. How is this possible? Here is Benson’s answer:

The soul appears to have two departments. There is (1) the ordinary activities; understanding, intellectual attention; emotion; and one kind of imperfect memory. These faculties are used constantly by every sane person, good or bad. All such words as ‘clever,’ ‘stupid,’ ‘good memory,’ &c., are all applied to this important but superficial department. (2) The real part of the soul – the immortal part that we take with us when we die- is that, to my thinking, which is called the ‘image’ of God. It is ‘capable of God.’ Here the real character resides; the real self. It is by this that we shall be judged. It is here, too, that the real will resides. The ‘character’ of this self is formed and deformed and reformed by its use of the more external powers I have called ‘(1).’ (page 7)

Let me try and put this in my own words: we have the ability to think, For this, we as adults, use words. People often ask whether there can be consciousness without words. There can be: after all, infants are conscious before they can either understand or speak. But the ordinary part of the mind, what Benson calls “1,” is the part of the mind that learns to use words and then sticks to them when it can, attaching labels with gay abandon to all which comes within its sphere. It is not that part of the mind which can become aware of the presence of God. It can talk about God, and even persuade itself that it sees, hears or feels Him.

But that is not the end: there is a part of the soul, which Benson says is “2,” which is able to be aware of the presence of God without words, with nothing else but will – that is, consciousness directed towards God. I shall call this the higher part of the mind, and refer to “1” as the lower mind. This distinction is well known in ancient philosophy: the higher mind was called the nous.

It is a mark of Monsignor Benson’s extraordinary wisdom that he saw that the higher part of the mind is hemmed in by the lower part. I think plants offer a good analogy. A plant has a higher level of being than a wooden stake, a fence, or any inanimate object which we use to train the plant. Here, “train” means to “form,” to influence how it grows and develops. Hence Monsignor Benson stated “The ‘character’ of this self is formed and deformed and reformed by its use of the more external powers I have called ‘1’.”

This is why a good education is so important. A bad education can mean that we cannot make use of our inherent good qualities of soul: our minds – and I would add, our emotions – can be so unruly that we cannot realise or bring to the surface the good qualities within us, namely, the image of God.

Benson continues, saying that we cannot always keep the lower intellect fixed upon God for the perfectly good reason that God created the intellect to do other work, e.g. to see the needs in your life and those of your dependents and to act on them. Benson says that when doing something practical like teaching a class, “… you are bound to concentrate all those powers (of the lower mind) upon the business in hand. To withdraw them, even to fix them on God, would be to misuse them; because God has given us them to arrive at Him indirectly with.” (pp.7-8)

When he says, “indirectly,” he means, I think, by preparing ourselves and our lives so that we can learn about God, and understand the need to practice being conscious of the presence of God. He interprets Brother Lawrence as meaning that: “… it is possible to keep (the higher mind) always fixed upon God – the deep inner self; so that when your whole intellectual powers are engaged in teaching, your soul is with God. ‘I sleep, but my heart waketh.’ But this requires effort.”

The little Brother Lawrence book deals with how to do this. Benson rephrases this in his own way:

Therefore (we should remember) at certain times to make deliberate intellectual acts of the Presence of God; and emotional acts of Love: and acts of memory in recalling His Passion &c. – all these are good, and tend to steady the deep inner self on God. Sin has affected every part of our nature – spoilt even the ‘image,’ so that our tendency is not even to keep that part of self fixed on God. Gradually, however as the work of sanctification goes forward, the inner self ‘(2)’ spends longer and longer periods with God; and its attention gets more and more intensified, and its control of the outer department gets more and more complete, until ultimately the real self never stirs from contemplation. Mary is always at His feet, while Martha does her business without distracting Mary: and every now and then herself comes in to Mary too. …” (page 8)