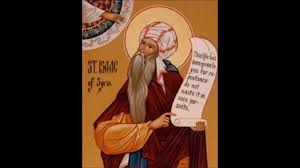

St Isaac the Syrian: Wonder and Amazement

The Feast of St Isaac the Syrian is celebrated by the Maronite church on 23 August. He was born in modern-day Qatar, possibly around 613. Qatar was then an important centre of Christianity. He became a monk. In about 676, he was appointed bishop of Nineveh (now Mosul in Iraq). However, he found himself unsuited to that office, and after only five months he resigned his See, and went to live as a monk. He was famous for his wisdom, religiosity, learning, and asceticism (he ate only three loaves of bread a week, with raw vegetables).

He dictated many thoughts, parts of which have been translated into all languages of the Christian world, including the European languages. but little is readily accessible. I will only sample his teachings here.

St Isaac tells us that: “Faith is the gate to the mysteries (rōze). What the body’s eyes are in relation to perceptible objects, so it is with faith in the case of the treasures that lie hidden to the eyes of the mind.” This is fundamental: Isaac seems to be speaking about a spiritual intuition (sukōlō) which is united to the One who is above both word and silence (3.1.11). There is something inside us which is higher than the thinking mind, and until we trust in it we cannot see with the “eyes of the mind.”

This may explain why a person of faith will be moved to wonder (tehrō) at the depths of the divine nature: we can never reach the end of God, in fact, we can barely even begin to contemplate him. Wonder is described as a bond placed by God upon the heart (7.33), meaning, I think, that when we obtain even a glimpse of God, our heart and our interest are awakened, and all we want to do for a time is to lose ourselves in His endless glory.

A sense of wonder stops us for a moment. It makes us sit up and drink in the vision, with all our heart and mind. Wonder is a sort of astonishment, but it not in the sense of “critical” or “disapproving.” It brings an awareness of the goodness of what we see, and that it is too big for our minds to contain. There is often, with wonder, a feeling that I have been privileged to see a miracle. Hence, St Isaac has this blessing for his pupils: “May your mind be filled with wonder at God, and the fire of His love shine in your soul, while it proceeds in meditation on the insights of His mysteries, toward the place which is above the world” (12.25). The very effort to meditate on God lifts the mind (1.8), perhaps because it demands the wordless intuition, which he also calls “meditation” (hergō, 1.14). This leads to wonder.

This meditation is a form of continual prayer, and prayer, St Isaac tells us, draws us to fellowship with God more than anything else (3.1.1 and 3.3.1). Prayer is perfect love and the perception of what is in God (3.4.1). It is worth repeating that: according to St Isaac, prayer is perfect love and the perception of what is in God.

The Dwelling of God

St Isaac was addressing monks, but his teachings can be adapted to the modern laity. Reading, or more precisely, contemplating Holy Scripture was central to his spiritual method. He stressed that one had to prepare oneself by prayer, and to read Scripture in a state of stillness. This all the more significant for us today, being contrary to the modern idea that anyone can just sit down and read Scripture like any other literature. If we admit a need for preparation it is only intellectual preparation. St Isaac says that the preparation which counts is the preparation of our entire person: our being. Scripture is not literature, it is revelation. How we read it depends on our being state at the time.

St Isaac draws on the Old Testament when he speaks about the “Shekhinah.” This is the glory of the presence of God, which appeared when King Solomon built the Temple in Jerusalem. A cloud of light, it was so powerful that no priest could remain before it.

St Isaac describes the vision of God to the soul: “It is like this for the soul which has been built upon virtue, when at the time of prayer it perceives this cloud which overshadows the intellect at prayer. … the one who prays is not able to complete the recitation of his prayer … (but) becomes tranquil and speechless in stupor (temhō) before the glory of the Lord, which is revealed by an intuition of the intellect” (8.8-9).

temhō, often translated as “ stupor, amazement, reverence,” is a second and deeper aspect of wonder. The late departed Mary Hansbury wrote: “ecstasy begins with astonishment or wonder (tehrō) and may lead to helpless amazement or stupor (temhō).” She goes on to say that the soul is struck into wonder by tehrō, and this feeling can be so powerful that the desire of the soul is fulfilled and the human spirit no longer has any movement (14). So rich a vocabulary did Syriac develop for the spiritual life: it even has two words for “wonder,” and the difference between them is the effect upon the soul.

By conforming our life to the divine, the higher becomes a pattern for the lower; the body changes from being a servant of carnal and intention into a vessel of the divine. St Isaac writes: “By stillness of the body and ceasing from this world, solitaries imagine the true stillness and the withdrawal from nature which will occur at the end of the corporeal world. By means of the mind, they are united with the world of the spirit. By means of meditation they are involved in the expanse above. Thus, symbolically, they remain continually in the future reality” (Hansbury, 18-20).

But the word which Hansbury renders as “symbolically” is a phrase – dab.Tuf.so, meaning “according to the type”, or “the archetype”. What St Isaac is saying is that when we begin to see with the eyes of the heart that the earth is modelled on the archetype of heaven, then by looking to that eternal reality we share in it. But for the world to more truly reflect the divine model on which it has been created, we must cleanse it of what is evil and build up what is good: this is our labour, our work.

Patience

St Isaac says: “Do not try to make your course run more quickly than the Divine Will wishes; do not be in such a hurry that you try to get ahead of the Providence which is guiding you – not that I am saying that you should not be eager. For someone to entrust himself to God means that, from that point onwards, he will no longer be devoured by anguish to fear over anything; nor will he again be tormented by the thought that he has no one to look after him” (125 and 126). He gives the warning: “Once someone has doubted God’s care for him, he immediately falls into a myriad of anxieties” (127).

There are many lessons here, but here is one: we are only as patient as our attitude to what we want, and to when we should receive it. If what we want more than anything else is God Himself, then we should know that He will guide us to Himself in His own good time. We have no right to expect anything else. If that is our attitude, we can wait, because all we want is One who cannot be neither forced nor compelled.

St Isaac was very practical, hence he taught his disciples that they had to begin prayer, and not wait until it was easy: “You should not wait until you are cleansed of wandering thoughts before you desire to pray. If you only begin on prayer when you see that your mind has become perfect and raised above all recollection of the world, then you will never pray” (118).

Neither should we fear that our offering to God is too small: “God accepts the paltry and insignificant things done with a good will for His sake, along with mighty and perfect actions” (136). In fact, we might ask: unless one can make small offerings and sacrifices with a good will, how can one perform a mighty work? St Isaac was indeed a master of the spiritual life.

“Love is sweeter than life; but even sweeter than honey and a honeycomb is an insight concerning God out of which love is born.” St Isaac.

revised 20 August 2021