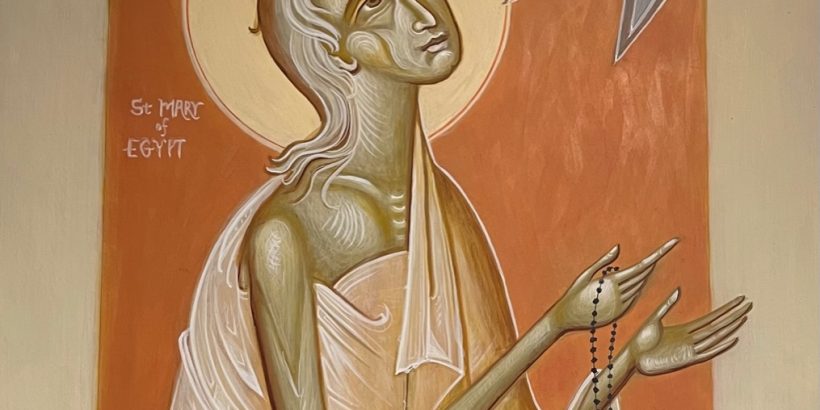

The icon of St Mary of Egypt with this post was written by a friend of mine: B(T)S.

I have previously mentioned Blosian meditation twice, in connection with Monsignor Robert Hugh Benson: http://www.fryuhanna.com/2020/10/02/mons-r-h-benson-spiritual-letters-part-i/http://www.fryuhanna.com/2020/10/14/monsignor-robert-hugh-bensons-spiritual-letters-part-iii/

The edition of his writing which I use is A Book of Spiritual Instruction (Institutio Spiritualis),Ludovicus Blosius, trans. Bertrand A. Wilberforce, ed. A Benedictine of Stanbrook Abbey, Burns & Oates, London, 1955 revision of a book first published in 1900

Francois-Louis de Blois,is known as “Blosius the Venerable.” “Ludovicus” and “Blosius” are Latinizations of his name. He was born at Donstienne near Liège, in October 1506, the son of Alain de Blois, of the nobility of Hainault. He was a page to Charles V, and in 1520 entered the Benedictine abbey of Liessies in Hainault. At age 21, before he was a priest, he was made coadjutor of the abbey, and two years later, when the abbot died, Blosius became abbot. He was ordained a priest on 11 November 1530, and made abbot two days later. So he was made abbot at the young age of 24. I doubt whether anyone can now say if this was due in part or in whole to family connections or not. But note that he became an abbot only 13 years after the date conventionally given as the beginning of the Protestant “Reformation.” It was a difficult period for Catholics and especially for monks, especially as Luther abjured his own monastic vows to become a layman.

Wilberforce says that Blosius was engaged in reforms and what we might call “monastic politics.” However, his spirituality was the driving impulse in his life. There is good reason why those who are called to the contemplative life should first of all, and often while seeking deeper spiritual experience, also test themselves in practical affairs. It is not good to seek the cloister as a way of escaping from the world. If one is to leave the world of busy people and tangled affairs, it is far better to do so after having conquered it: to show that one can engage with it while retaining spiritual poise, and then, to withdraw from a position of strength.

The editor also notes that Blosius has been called “the Doctor of the presence of God.” This means “one who teaches how to approach the presence of God.” Wilberforce continues: “Union with God was the leitmotiv [recurring theme] of his life … he knew that such was to be obtained only by prayer and self-discipline.” He always spoke of the “spiritual ascetic,” This is known, in Latin, as the asceta spiritualis.

The introduction is very good, and as it provides a sort of bird’s-eye view of Blosius’ writings, I shall quote it here: Wilberforce states that the “chief excellence [of Blosius’ writing] seems to me to lie in this – that Blosius directs the eye of the soul away from itself, its own miseries and shortcomings, to God, his beauty and perfection. … If souls aiming at holiness can only be got to look at God instead of themselves, the battle is more than half won, victory becomes certain.” (vi) I shall pause for a moment: this idea of looking at God rather than ourselves is profound. And it can be developed further, when we do eventually consider ourselves, as we must since we have to eat, drink and find safe lodgings, we can strive to do so in the light of the presence of God. It is as if we try to look at our own selves from a higher perspective, that of the Will of God.

Wilberforce continues: “By contemplation is meant the raising up of the mind to God by intuition, accompanied by most ardent love. We mean by intuition a mental sight or view of the mind seeing truth without the intervention of argument, testimony or reflections. … It is an experiential perception of God, not merely speculative, practical as well as theoretical; it is a union of will with him, and not a mere intellectual apprehension.” (viii) That is, one cannot think or reason one’s way to God. These are useful in preparing us for the path, but it is like driving to the airport and then expecting to fly overseas in our car. Our ordinary faculties, including our reason, can take us a certain distance, but then we have to park it, alight from the car, and embark on the plane. In the case of contemplation, the flight is made with “intuition.” This word comes from the Latin in with tueor, that is, to look or observe in. We see the sun and we know immediately that it is the sun. I do not need to compare it with pictures in meteorology books. This intuition is also practical, as the editor states, because it affects us in practice. If our “intuition” of God is merely a curiosity, then it is not true intuition, it is mere philosophy: good in its place, but futile outside of it.

Having said this, Wilberforce continues: “The ordinary contemplation means a close union with God in intellect and will, which is the result of faithful correspondence to the grace he bestows according to the ordinary laws of his providence in the supernatural life.” (viii-ix) This is a good, even a wonderful thing. The grace of God is never to be rejected. A person who, for example, attends the Divine Liturgy, and feels moved to a “close union of intellect and will” with God, has received the early fruits of contemplation. That person is already experiencing the supernatural life while still fulfilling his duties on earth.

Then, he adds: “Extraordinary contemplation is a singular and miraculous union of mind with God, by simple intuition, accompanied with most ardent love, exceeding the ordinary laws of his providence in the supernatural life.” (ix) It may be that this element of love gives us the power – or enables us to be channels for that power – which works small miracles, like showing patience where previously we never did, forgiveness where once we only knew resentment, sympathy where once we only knew stubborn judgmentalism, and so on.

I close this first part with two important comments: “We should no more presume to ask for extraordinary contemplation than for the gift of miracles or prophecy.” (x) i.e. because of humility. But for the grace of ordinary contemplation, we can and even should seek from God. Wilberforce concludes with this thought: “The gift of contemplation increases charity, and therefore it is lawful to be desired.” (xi)