Part one and two appear at http://www.fryuhanna.com/2022/01/28/ad-orientem-liturgies-part-i/

http://www.fryuhanna.com/2022/02/04/ad-orientem-liturgies-part-ii/

The Maronite rite commences the liturgy of the Eucharist with an access to the altar (l-baytokh Aloho 3elet). It is specified only that the priest approaches the altar. In the great majority of churches, the priest approaches the altar from the steps, i.e. he and the people are facing in the same direction. I only know of one church where, due to the basing of the church on the layout of a Brazilian church, the priest approaches from behind the altar: Our Lady of Lebanon, Harris Park.

This relates back to how, in the original Maronite liturgies, it seems that the Liturgy of the Word was held at the bema in the middle of church or, as at Saydet Elige, inside the front entrance. That is why the priest opens the liturgy chanting that he has come to the house of God, but when he moves, with the congregation, from bema to altar, he now chants that he has come to the altar of God. There was an actual and unmistakable change of location.

Then comes the second portion in the Maronite liturgy where the priest crosses his hands over his breast, bows to the left and then to the right, and asks the congregation to pray for him. What I find quite fascinating is that of each of these prayers, Fr Archdale King states that the priest is moving his head in the form of a cross: Archdale King, The Rites of Eastern Christendom, (first published 1948 by the Catholic Book Agency, Rome, and republished in 2007 by Gorgias Press, Piscataway), volume I, 260 and 265.

The veracity of this has been confirmed by a Maronite text provided to me as recently as yesterday (24 February). It is titled La Sainte Messe selon le Rite Maronite by the Maronite Church of Notre-Dame du Liban, 17, Rue d’ilm, Paris, with a nihil obstat dated 10 December 1918. It states, on p.7, Arrivé à l’autel, le prêtre s’incline profondément, fait avec la tête un signe de croix (Having arrived at the altar, the priest bows profoundly, (and) makes the Sign of the Cross with his head). It is silent as to how the priest proceeds from the lectern to the altar.

This is a rather unique gesture so far as I know; not so much a gesture as a sacred movement. By the use of the head, it is more than making the Sign of the Cross in the air, it is a partial identification of the entire person with the Lord. If the priest has become a symbol of the Cross, then he has become a symbol of the Lord, and as the Lord was hung from the Cross, he has become a symbol of the possible appearance of the Lord. The priest prepares himself to be the instrument of the Lord in so thorough a way that it becomes a mystical identification. However, I believe that modern Maronite priests are unaware of this.

This raises questions about the difference between the Latin and the Maronite liturgy through the Liturgy of the Eucharist. it may be there are profound differences which have been papered over because of Latin desire to assimilate all Eastern Catholic Churches to their own model, and an Eastern desire to cooperate with this. Part of this desire is found in an inability to imagine that there can be any other legitimate approach to the Eucharist than the one presently favoured in Rome. However, of all the Roman approaches to the role of the priest, there is no question: the older view of the priest as an alter Christus is much closer to the Maronite than the new one which sees him as a presider of a people’s Mass.

This makes me wonder whether the question of Ad orientem can be productively discussed without considering the role of the priest in the liturgy. It is not just a question of role, like an actor in a play – it is more a question of who the priest is, especially in the liturgy.

However, when we compare this with the traditional Latin Mass, the first significant point of departure is that there is no access to the altar after the Creed: the priest is already at the altar. He then turns to the congregation and extends his hands saying “Oremus,” “Let us pray” and reads the prayer named the Offertory. He then unveils the oblations.

Now, other than for the “Oremus,” the priest in the Latin liturgy is facing the altar. The Offertory is one prayer alone. But the Maronite liturgy has the chant of access, then a hymn, an incensing of offerings (which comes later in the Latin liturgy), and two prayers, in one of which the chalice and paten are held before the congregation. This is followed by another hymn, this one in honour of Our Lady. Just as there are two feasts of Our Lady celebrating her connection with the Eucharist (Our Lady of the Harvest of Grapes, and of Wheat), so too in the Maronite liturgy she is connected to each Eucharistic celebration through this hymn. The basis of the connection is, of course, that the Eucharist is her Son.

Also, the Maronite liturgy differs in that on Sundays and feasts, the offerings are usually brought to the steps of the altar by a delegation from the congregation. In the traditional Latin rite, the oblations are on the altar, and there is no procession.

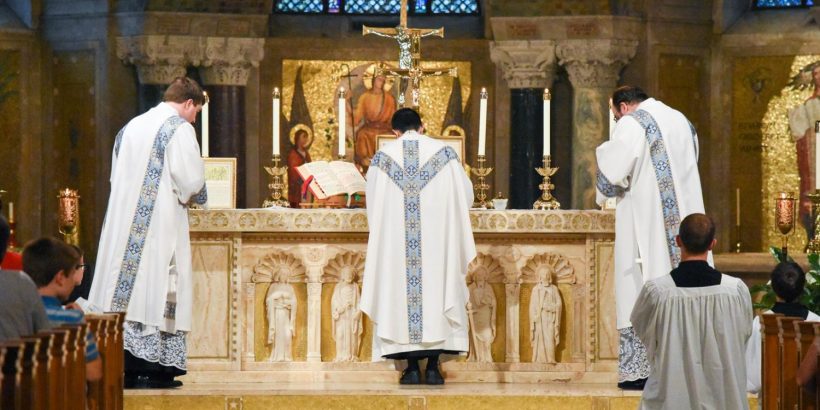

Now, something important to recognise is that at all points in the Maronite Pre-Anaphora, the priest is facing the altar. Sometimes the people are facing his direction, and sometimes not, but the priest, who embodies the Cross, is always oriented towards and serving the altar.

So, the Maronite “Pre-Anaphora” and the corresponding parts of the traditional Latin are effectively beyond comparison. The theology of the priesthood, the relation in space and spirit of the Eucharistic Liturgy to what has preceded it, the length and actions of this section, and the actions of the priest, are quite different.

Now, if what Fr King says about the liturgical actions of the Maronite priest is correct, then the result should be that the priest effaces himself during the liturgy, he should not exhibit singularity, he should no promote or otherwise highlight his own personality. But once more, the differences in orientation seem to me to faithfully represent the inherent nature of the liturgies.

Thank you for these articles Father.

We ceased having parishioners process the gifts to the altar due to the consecrated nature of the sacred vessels. Consequently, only subdeacons, deacons or religious carry the gifts.

The greater catechetical problem we are facing is the congregation’s understanding of the presanctified gifts: virtually everyone crosses themselves and/or bows reverently when the gifts are carried in procession to the altar at the pre-anaphora. That’s not really where our dilemma is. Rather, when the deacon later carries the ciborium WITH the Eucharist to the back of the church to give Communion to the elderly, choir, etc…. nearly NO ONE bows or crosses themselves, as if oblivious to the Real Presence of our Lord. Despite the deacon carrying the ciborium at head-level!

I have attended twice Maronite mass in the Paris Maronite Church (it’s the Maronite cathedral in fact, the church building was built by Jesuits). I found it’s really latinized now, in these two masses they only mention western theologians in sermons and the liturgy lasts only about 1h15, they only have Maronite Mass every Saturday evening (anticipate Sunday mass).