I am pleased to announce that, on 29 October 2020, a small group of young Maronites placed a good quality recording of the Aboun d.bašmayo (the Our Father in Syriac) on Youtube. The recording includes a literal English translation with the Syriac in three scripts: Syriac, English, and Arabic. You can watch it here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zOucQNlzN8A

And don’t just watch it: learn it. Make saying the prayer in Syriac a regular part of your prayer life. It will soon become not only a part but – because it is so rich – it will also become the spirit of your prayer life. St Jacob of Serug wrote of the “Our Father”: “The prayer which the Son of God taught is full of wealth, and by it you know who and of what importance you are.”

Then, I might suggest, don’t just learn it alone but learn it in and with your family, with your friends, and in your clubs. God willing, one day we will be learning it as a Church.

There is no reason to learn Syriac except for reasons of faith. That makes it special. You will not receive a single cent for being able to pray in it. You will not be able to pray publicly in Syriac during the Mass at the local English-language Latin church. Or in any Latin Church. It is not so hard but neither is it so easy to pick up. To learn the Aboun d.bašmayo you have to feel the desire. That too is another reason why it is a special way of praying.

But there is more: if you go to France, for example, then while you cannot speak French there is a certain difference between yourself and the people which will appear whenever you open your mouth, or they open theirs. If you acquired French, however, there would immediately be a sign of unity between you and them. This is part of the reason people like to hear foreigners trying to learn their language. It shows a wanting to share in something of theirs: their culture, their way of life, their perspective on the world.

So too, I would say, learning to say the Aboun d.bašmayo in the very language Our Lord used is a sign of unity with Him. It certainly marks a desire to be express unity with Him. Even more than learning French, where there are many people you can speak to in that language, many places to visit where it is spoken. But with the Aboun d.bašmayo there is only person you can speak to: God. There is only one place you can visit: His Presence.

Syriac is not our ordinary language. No one you know speaks Syriac. You only ever hear a few sentences of it, and that is practically always at church. Would it not be a sign of Maronite unity if all Maronites, throughout the entire world, learnt to say the Aboun d.bašmayo and prayed it in every church service, in every meeting of our societies and sodalities? Could you not imagine people asking: what is that? And being pleasantly surprised when they learnt that we are praying that prayer in the language Our Lord used? Would that not be a unique and wonderful marker of being Maronite that we pray this prayer in Syriac?

It would be something if our schools and churches taught all their students this prayer. It would be an aspect of Maronite education which was never erased. Even if someone left the faith when they left school, they would always recognise it, and – more likely than not – also remember it. Because it is so distinctive, it would always be a reminder: “You are a Maronite, don’t forget. Out of love for your eternal soul your parents had you baptised.” It would be like a token of affection that was always waiting to be uncovered. It would stir old memories, arouse old feelings. It would differentiate the Maronites from the Latin Catholics, in a good way, giving us something to be proud of. It would be a truly spiritual way to pray the “Our Father,” far better than the holding of hands which many people object to and even more think of as a gimmick forced on them.

Because Syriac is not the language we speak, we all need to make an effort to say it. Even someone like myself who has been praying it for very many years still has to make a mental effort to get all the sounds, all the vowels right. It attracts a careful attention to the fact of praying. It always invites investigation: what is this word? What does it mean? Why does the Syriac say “as in heaven, so on earth,” placing heaven before earth? And so on, and so on.

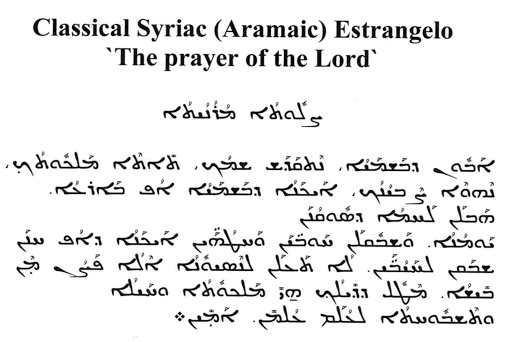

Finally, I will just note that Syriac is a dialect of Aramaic. The Aramaic language was spoken and written throughout the Ancient Near East for hundreds of years. There was never any Aramaic script, they just wrote it in the script of other languages. The Phoenician script, which was also adapted for Hebrew suited this purpose very well. And so Aramaic came, by the time of the Lord, to be written in what they called “Hebrew characters.” But during His lifetime, or a just a little before, a new script was invented in or around Edessa, in modern Turkey. When the language is written in that script, it is called “Syriac.” So Syriac and Aramaic were, at first, the same language. Only with time did the two start to diverge. But even so, they are still clearly very close to each other, and often practically identical.