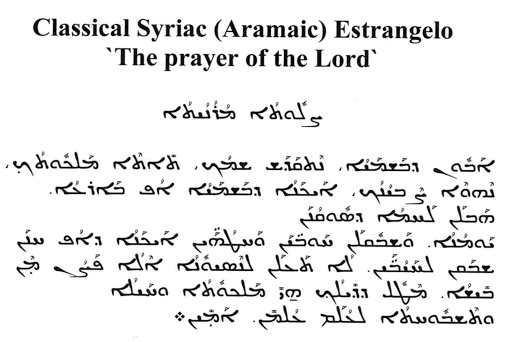

PART ONE: The “OUR FATHER,” Syriac transliteration and literal English translation

Aboun d.baš.ma.yo

Our Father, who (is) in heaven

net.qa.daš šmokh

Let it be hallowed, Thy name

tee.te mal.kou.tokh

Let it come, Thy Kingdom

neh.we Seb.yo.nokh

Let it be, Thy will

ay.ka.no d.baš.ma.yo off bar.3o

As in heaven, so on earth

hab.lan laH.mo d.soun.qo.nan yow.mo.no

Give us (that) bread which is necessary, today

waš.buq lan Haw.bayn waH.to.Hayn

And forgive us our debts and our trespasses

ay.ka.no doff H.nan šba.qan l.Ha.yo.bayn

As we have forgiven our debtors

w.lo ta3.lan l.ness.you.no

Lead us not into temptation

e.lo fa.So men bee.šo

But deliver (us) from (the) evil (one)

me.Toul d.dee.lokh mal.kou.to

For Thine is the Kingdom

w.Hay.lo w.teš.bouH.to

and the power and the glory

l.3o.lam 3ol.meen, Ameen

For ever and ever, Amen (Let it be made firm)

Notes: the number 3 represents the Semitic consonant ain, also spelt ayin. If you do not know this consonant, just ignore it.

The letter š represents the sh sound in a word like “shape.”

The capital H represents the Semitic consonant Het. If you do not know that consonant, treat it like an ordinary h.

The capital S represents the Semitic consonant Sade, If you do not know that consonant, treat it like an ordinary s.

PART TWO: Notes

The very first word here is “Aboun”, literally, “Father, our.” It commences with this key word. The English commences with “Our,” but the Greek and Latin with “Pater” (Father), and the Arabic, like the Syriac and Latin, with “Father” (abānā). It is just the way the languages are, yet it is good to be aware of the different nuances presented by each language.

Then, the Syriac, like the original Greek, has “As in heaven, so on earth.” This is the order in almost every language, except English, and some older English translations did have this. This is a very significant difference: the original order expresses the belief that all in creation begins from above, and then is reflected on the lower plane. This is intimately related to the idea of typology, in fact, it is one aspect of the teaching of typology.

The basis of typology is this: we and our world we created according to divine models, and we reflect them more or less imperfectly. The more imperfect or distorted our reflection of the divine, the further we are from God. For more on typology, see Joseph Azize, An Introduction to the Maronite Faith, 2nd edition, Connor Court Publishing, 2018, 185-194. Forget what you think you know about typology: the genuine article is a comprehensive view of the creation, the relation between God and Man is theology and in history, as well as the basis for a far-reaching spirituality.

When we follow the Syriac and pray: “Give us (that) bread which is necessary, today,” we are not just saying “give us this day our daily bread.” That is an odd phrase: if we mean give us today our daily rations or pay or whatever, we say: “Give us our daily food.” But “give us this day, our daily bread,” is a puzzle. I suspect that the ancient translations which have “give us this day our supersubstantial bread” are more correct.[1] The point is that the Syriac has “our necessary” bread; and I think that must relate to the idea of supernatural bread, i.e. the Eucharist above all, but the teaching of God as a whole, for man does not live on bread alone, but by every word that comes from the mouth of the Lord (Matthew 4:4 picking up Deuteronomy 8:3).

Interestingly, this is another expression of the idea that all begins with God in heaven, and can then be manifested down here: it is saying we are here on earth, and ask You, Lord, for the heavenly food which we need each day. This is the highest food. This is a typological motif.

Then, the Syriac has “And forgive us our debts and our trespasses …” Now, Matthew 6:12 has, in Greek, kai aphes hēmin ta opheilēmata hēmōn, which means “and forgive us what is owed by us…” In Aramaic this word for “debt” also meant “sin.” Perhaps because this was not so clear in the original Greek of the New Testament, the Syriac makes this even clearer by using two words: Haw.bayn waH.to.Hayn.

There are two very similar words in Syriac: first, Ha(w)b, “a debt,” which in the emphatic is written HaWBō. The second word is Hu(w)bō meaning “love”, which in the emphatic is written Hu(w)bō. They come from different Syriac roots. The root for Ha(w)b “debt” is Hwb, but for Hu(w)b “love” is Hb.

The next noun in this line is from HTōh meaning “sin.” So the Syriac makes clear we seek forgiveness for both our debts and our sins.

Is it deliver us from “evil” or from “the evil one”? What is the real difference? I think that the original sense was almost certainly “the Evil One.” that is a large question, and involves looking at the context, and also the possibility that the Our Father in Matthew 6, is designed, at least in part, as the ideal prayer against temptation, and that the account of the Temptation of the Lord in Matthew 4 is the reverse of the Our Father.

[1] The word used in the Gospels of Ss Matthew and Luke, and which is usually translated “daily” is epiousios. One authority writes: “epiousios … some Fathers understood the word as supersubstantialis, super-natural, and referred it to the eucharist.” Max Zerwick and Mary Grosvenor, A Grammatical Analysis of the Greek New Testament, 5th revised edition, 16.

Wonderful❗️I commit to learning this🦚