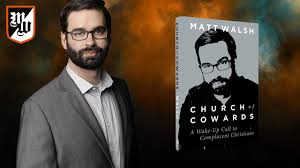

Part two of my review of Matt Walsh’s Church of Cowards was, in parts, a meditation on Walsh’s insights. This third and final part will be more of a traditional review.

We are up to chapter 9, “In and of the World.” This deals with the media, and makes the point that not only is today’s media hostile to Christianity, but to use as much of it as we do “prevents us from living an authentic human existence and reduces us to the status of spectators” (130). In other words, we are passive before the anti-Christian activism of the electronic media. Walsh well describes the insidious way we become addicted to these media, the excuses we make for ourselves, and how we now have an infantilised language: “to say nothing of all the pornography” (133).

One of his more provocative assaults is that we are losing “intrapersonal existence,” as we pour half-baked ideas into the public arena (134). He is, I fear, right: we are not spending enough time considering our own thoughts and feelings, critiquing them, and formulating them. I am not sure what he means by saying that “nothing you do is morally neutral,” and applying this to clothing, diet and how we speak (135). It is true that entertainment is a “force” (136), but I fail to see why watching something which is neither improving nor immoral is not morally neutral. He notes, quite correctly, that “we must establish boundaries between ourselves and the world … (but instead we) give ourselves no time to think, or pray, or meditate on the deeper truths of life” (137). There is also a splendid critique of the public school system (137-142).

“Disorganized Religion” in chapter 10 begins with the phenomenon of people saying that they are “spiritual” but not “religious.” It often presents a false dichotomy between “Jesus” on the one hand, and institutional religion on the other (146-147). Although many self-styled Christians avoid church today, they are departing from the ancient teaching and tradition which goes all the way back to when the Lord Himself founded His Church (149-152). Walsh points out that ritual is natural, and “human beings are ritualistic” (153-154). This is quite important, in fact, I think it more important than even Walsh himself understands. If we change the liturgy cavalierly, we announce in letters of fire, that everything is up for change in accordance with personal desires. The teaching and even the liturgy provide direction, and as Walsh rightly says: “Man is also a creature in need of direction and clarity because he is a creature prone to rebellion and confusion. That is why organized religion exists. It is not perfect because it is not only made for man but, by unfortunate necessity, run by him. But it is wholly preferable to any other available option” (154). At the end of this chapter he calls for a “spiritual crusade” (156).

Although there are some brilliant insights in the eleventh chapter, “Cheap Repentance,” it raised more questions for me than any other. This is chiefly because of the question of “mercy.” Walsh states: “A man is only merciful if he forgives the unforgivable …” (159). I am not sure that is right. A merciful judge does not have to forgive, he might well state that the prisoner has to be punished, but then mitigate that punishment. Neither am I sure that “Mercy is only mercy if it is entirely undeserved” (159). That, it seems to me, is indulgence. In fact, in James 2:13, we read: “… judgment will be merciless to one who has shown no mercy; mercy triumphs over judgment.” This tells against Walsh.

I think the problem has partly to do with when we speak about the mercy and justice of God, we are approaching infinite qualities which we cannot comprehend. And so, although everything in God is a unity, we who have only partial sight, see contradictions where there are not and can not be any. But I also think that part of the issue we have today is understanding the concept of grace. We tend today to assimilate the ideas of grace and mercy. But they are quite different perspectives, and the concept of grace has been developed, carefully, by great saints to show how while nothing we can do can merit the grace of God, yet it is supplied, although we have free will and can reject it. Equally, we can seek and accept it. I am sure this will not be my final understanding of these mysteries: I am really floating a hypothesis. But could it be that the great mercy of God is first of all shown in His provision to us of all that we have, all our possibilities, and then, within that merciful framework, there is justice. This would make sense of James 2:13. It would also explain how something is expected of us: we do have duties and responsibilities, and yet we cannot deny the reality of divine mercy.

However, Walsh is quite accurate in his critique of “false self-esteem” (160-161), and that the proper attitude for us is to esteem God and be grateful. He is then entirely correct, I suggest, to say “through … repentance we begin to experience God’s mercy in its fullness” (161). If that is right, yet it is not what he was saying above. Finally, Walsh’s treatment of the Parable of the Prodigal Son is uniformly excellent: we do indeed vacillate between the positions of the two brothers (169).

The final chapter, “Heaven for Everyone,” nicely wraps it all together. This has been a book about and against modern despair, and the remedy is faith and the virtues of the faith, especially courage, hope for heaven, desiring only what we need and what is good – and so, conversely, avoiding the multiplication of blind, selfish desires (171-173). This involves understanding the necessity and the value of suffering: a counter-cultural goal indeed (174-176). The quotation from my second patron saint, St John Henry Newman, is apt and deep (178-180). It comes down to this: we have to work at “finding joy in what is holy and sacred. … The souls in Hell are only in Hell because they’re in no condition for Heaven” (181). In the end, we obtain what we have chosen.

As I have several times stated, my assessment is that this book is deep, timely, and well-written. It is accessible in a way most theology is not, and yet it is one of the best modern works of theology I have read. Perhaps Walsh does not yet fully comprehend the concepts of grace and mercy, or of the practical importance of the liturgy in the formation of the Christian soul. But then, who really does? Life is a pilgrimage, and this book is a most valuable addition to the pilgrim’s rucksack.

Fr Yuhanna (Joseph) Azize, 20 August 2020 (Feast of St Bernard)